The Imperiled Monarch & What San Franciscans Can Do

Monarch drinking nectar from narrow leaf milkweed, Asclepias fascicularis, which blooms in mid-summer as generations move north and toward the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Many people are concerned about the plight of the monarch butterfly once they learn that the Western Monarch population has decreased more than 99% since the 1980s. San Francisco and Bay Area residents are asking how they can help and are often surprised to hear that the mantra “plant milkweed” not only doesn’t help along the coast, it can actually be harmful.

Why is that the case, and what can coastal residents do to help instead? Read on to learn more!

The Magnificent Monarch Migration & San Francisco Safe Haven

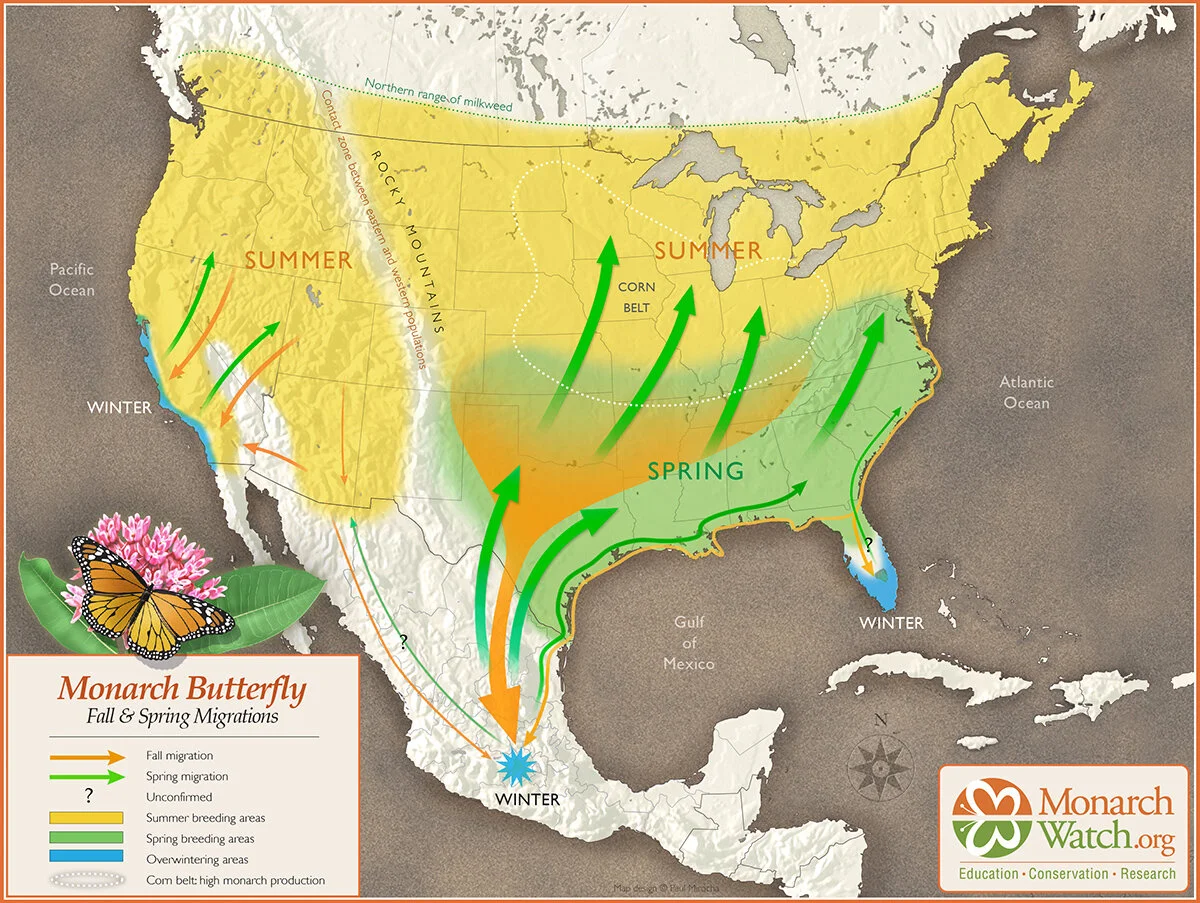

To understand what solutions there are for monarchs, it helps to learn about the butterfly’s life-cycle, including the incredible migrations that monarch populations undertake. Monarchs are native to the Americas with two distinct populations on each side of the Rocky Mountains. The Eastern and Western populations have different migration patterns and both spend the winters clustered in tall trees to rest. Although these populations “overwinter” in different locales, they have similar lifecycles.

The monarch migration is not undertaken by a single generation of adult butterflies, but by up to four successive generations. The population that spends the winter along the California coast and here in San Francisco is the longest-lived, having been the last generation to emerge at the end of summer and migrate to groves of trees along the coast. The adults cluster together, hanging from trees and venturing out on warm days to feed on nectar plants. In early spring, adult females begin the migration inland and north, continuing to feed on nectar plants and seek milkweed on which to lay their eggs.

During the spring/summer breeding season, the monarch migration historically followed the milkweeds inland as they emerged along waterways and stream courses. Then, breeding in quick succession, a new generation emerges every 4-6 weeks and moves north and east to find emerging milkweed. They travel past Mt. Diablo, through meadows in the Sierra Nevada mountains, and into Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. The last generation of the year, or super generation, begins the migration south and towards the coast to rest for the winter. The super generation females begin the cycle again in the spring when they venture out to find milkweed on which to lay their eggs.

Over the past few years, the number of sightings have plummeted compared to what was once millions of monarchs in these migrations, described as an “orange tide” by Mia Monroe, Western Monarch expert and Xerces Society representative.

San Francisco historically had several overwintering sites, including at the Presidio and Fort Mason (although no overwintering monarchs were observed in 2020/2021). On warmer days, overwintering adults will fan out into adjacent neighborhoods, seeking large, nectar-producing flowers that are available over the winter. Large butterflies need large flowers, and have been noted in iNaturalist nectaring on flowers including Callistemon, Tithonia, Lantana, Escallonia, Mock Orange, Salvia, Zinnia, Verbena, and others.

San Francisco also has several “bivouac sites” — rest stops along the migration route, where monarchs can pause to wait out a hot spell or smoky period. Golden Gate Park and Stern Grove are important bivouac sites in the city.

Monarch overwintering site at Rob Hill in 2016, the Presidio/photo by Liam O’Brien.

The Role of Milkweed

Milkweed is a critical food source for monarch caterpillars. In fact, milkweed is the only plant these hungry caterpillars can eat. Having a specialized host plant is very common among butterflies and other insects. Milkweed’s thick milky latex sap contains plant toxins called cardiac glycosides that make the larvae and adults poisonous to most predators (birds and some mice). The bright contrasting orange and black colors help predators learn to avoid eating them.

So why shouldn’t we plant milkweed along the coast? And if we live inland, does it matter what kind of milkweed we plant?

A tiny monarch caterpillar munches a hole in a milkweed leaf.

Do not plant milkweed along the coast where wild monarch populations overwinter. Milkweed produces flowers in summer and new growth throughout the growing season when females need it for laying their eggs. However, milkweed planted outside of its historical range could disrupt the monarch’s long-standing migration and breeding patterns. If an overwintering butterfly along the coast encounters milkweed (often sparsely planted) and lays eggs, the resulting offspring would likely not have enough milkweed to grow into a healthy adult butterfly. They may also be left behind by the migrating butterflies, which not only fragments the population but also exposes non-migrants to diseases and new weather patterns such as cool, heavy fog.

Do not plant tropical milkweeds (Asclepias curassavica and others) if you garden more than 5 miles from the coast. Disease build-up is very high among milkweeds that don't go dormant, leading to high monarch butterfly mortality and unhealthy plants. Instead, consult CalFlora and local native plant nurseries to find milkweeds that are native to your location. Narrow leaf milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis), showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa), and Indian milkweed (Asclepias eriocarpa) are the most common nearby native milkweeds. Most experts agree: plant native milkweed where it was commonly, historically found.

Monarch drinking nectar on Pacific aster (Symphyotrichum chilense).

A Migration Phenomenon in Peril

Much has been written about the causes of western monarch decline, and we are still learning more every day. The biggest factors that threaten monarchs — as well as other butterfly populations and insects in general —are intensive agriculture, habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change.

We depend on food grown in California’s Central Valley to provide fresh produce to much of the U.S. and beyond. Large swathes of land have been given over to single crop monocultures, limiting biodiversity. What’s more, agriculture has become increasingly dependent on fertilizer and pesticide use as soils become depleted of their live-giving resources. Although many farms are organic, and some have planted monarch habitat, we need more farmland that integrates healthy insect populations.

Climate change is disrupting the habitats and ecosystems that all living creatures — including butterflies and people — depend on. The greatest threats to monarchs from climate change include warmer days in early spring that cue butterflies to leave overwintering sites early, fires and smoke that sweep through California when the last generation is migrating, and more extreme fluctuations in weather, such as storms and drought.

Wildflowers native to San Francisco bloom along Sunset Blvd on Earth Day 2021.

What Can San Franciscans Do?

San Francisco may have the highest density of backyard gardens in California, providing food and rest stops for the western monarchs as they float overhead on their long journey. If you have a home garden or even one planter, you can become part of a “Homegrown National Park”, a powerful tool for biodiversity, climate resiliency, and conservation.

Here are many more ways you can help:

Help rebuild healthy ecosystems for monarch butterflies by planting local, organic native plants. This will also help other western butterflies and insects in general — all experiencing serious declines.

Ask your nursery if they use pesticides, and support local nurseries that don’t spray their plants. Nursery plants are often sprayed with pesticides such as neonicotinoids and even organic pesticides, such as BT. The pesticide impact on monarchs is much bigger than previously thought.

Keep your dinner plate pesticide-free as well! Support organic farmers, and advocate for agriculture that includes wildlife habitats.

Create nectar way-stations along the coast by planting large flowering nectar plants, especially those that bloom in fall, winter, and spring when monarchs are migrating to and from overwintering groves.

Make peace with weeds in your garden, and hand-pull weeds rather than using herbicides — you may be surprised to learn that many weeds are also butterfly host plants. Xerces Society has some useful resources for reducing pesticide use in your garden.

Join community science projects like the Western Monarch Count, and help contribute to our growing understanding by making iNaturalist observations where you live.

Advocate for additional research and endangered species status to support the monarch. Xerces is supporting legislation in 2021 to increase protections for monarchs.

Discover if there are any important overwintering sites in your neighborhood and help ensure that these are protected.

Talk to others about what you’ve learned, and remember that climate change and biodiversity loss are interrelated. The solutions to rebuilding our ecosystems and creating climate resiliency are the same.

Bring your friends and family, and join us — volunteer to help Nature in the City projects restore healthy ecosystems and mitigate the effects of climate change. Let’s make our gardens and public open spaces into local wildlife corridors — safe and welcoming oases for monarchs, pollinators, and birds — places for us all to learn up-close and enjoy!

Is There a Future for Western Monarch Migration?

Experts in the monarch community are actively discussing whether the western migration will continue with such small numbers, and whether the future of monarchs is in smaller localized populations. School and community garden groups in the San Francisco Bay Area, Santa Cruz, and Los Angeles are nurturing localized monarch populations by rearing caterpillars in their gardens and garages. We’re not sure if this helps or hurts wild populations.

What’s more, there are varying views on milkweed: whether milkweed abundance is contributing to the monarch decline or whether it matters which species people plant. Some ecologists are actively searching for California native milkweeds that emerge earlier to better sync with monarchs leaving overwintering sites early.

With so much at stake and no clear answers, the course for conservation is not yet clear. Nature in the City hopes to engage in these conversations over the coming year and will provide more information as a consensus (hopefully) emerges in the scientific community. Stay tuned for Part 2!

Appreciation and Further Information

Thank you to Mia Monroe, Liam O’Brien, and Catherine Chang for your help with background and new ideas for this article. If you would like to learn more, check out the links above as well as these resources:

- by Amber Hasselbring and Laura Castellini